10-year marker of the end of banking secrecy: Seeking a healthy balance between confidentiality and transparency

17/11/23

The year 2023 marks the 10th anniversary of the end of the banking secrecy in Luxembourg. The country’s professional secrecy provisions, including the banking secrecy and the goal of protecting private data from unauthorised access and use was deeply rooted in the Luxembourg law, since the 19th century. In April 2009, G20 Leaders took action to end the bank secrecy. Four years later, in April 2013, prime minister Jean-Claude Juncker announced that the Grand Duchy will relax its banking secrecy laws. What led to the abandonment of this long-established value of privacy law?

Financial markets were shaken.

Let us put the developments occurring in 2013 into the economic context of the time. Almost fifteen years ago, the world economy suffered the worst recession since World War II. The period was economically marked by the subprime and sovereign debt fund crisis. The GDP shrank by 3.5% in the US and the EU and by 7.1% in Japan, in 2009. The economic situation worldwide was marked by rising unemployment rates, a collapse of the world trade and decreasing consumer and business confidence. In an attempt to stabilize financial markets and reignite growth, the policy response in most developed countries consisted of providing public funding and fiscal stimulus packages. Both measures were weighing heavily on the governmental budgets. The economic outlook was gloomy.

An additional and most needed response to the financial crisis to achieve greater stability was an overarching reform of the regulation and supervision of the international financial system. One important building block of this reform amongst several others was the fight against tax evasion. This objective was pursued by strengthening the international tax cooperation and tightening the legal framework to combat money-laundering, corruption, financing of terrorism, and drug trafficking. The purpose was also to improve the governments’ fiscal capacity through higher tax revenues, which would in turn would support the financing of the fiscal stimulus packages. Increased tax scrutiny was brought on by most EU tax authorities to close budget deficits.

The development towards greater transparency also picked up momentum because not only Luxembourg, but also several Swiss banks fell victim of fraudulent data activities. A number of data thefts led to the situation that customer account data of private banks ended up in the hands of foreign tax authorities who took these cases as an opportunity to start investigations and tax audits.

The foundations of the Luxembourg banking secrecy

The Professional Secrecy Law, including the banking secrecy, is more than a century old and codified in article 458 of the Luxembourg Criminal Code, as well as article 35 of the law on the profession of lawyers, dated 10 August 1991 and article 41 of the Law on the Financial Sector dated 5 April 1993. On this statutory basis, the unlawful disclosure of private data is considered a criminal offense in Luxembourg, and the professional secrecy cannot be waived by the client. Prior to the changes occurring in 2013, the protection of data privacy was basically unlimited. Stemming from the 19th century, the concept represents a long-established principle in Luxembourg, and existed even before the financial centre started to develop. Therefore, the objective of protecting the citizens’ privacy has historically been broad and went beyond the protection from data access of foreign tax authorities.

Whilst the strict banking secrecy law fostered the growth of the private banking sector in Luxembourg, it cannot be considered to be the foundation for the private banking business model. Yet, in the early 2000s, Luxembourg private banks were serving mass affluent customers from neighbouring countries to a high extend, such as Germany, France, and Belgium.

An important development towards greater tax transparency in the EU

An attempt to increase the tax transparency within the EU was made through the EU Savings Directive 2003/48/EC dated 3 June 2003 whose aim was to enable an effective taxation of interest payments made in one EU Member State to beneficial owners who were resident for tax purposes in another EU Member State in accordance with the laws of the country of residence. The taxation was mainly ensured through tasks carried out by paying agents.

Following the Council Directive 77/799/EEC of 19 December 1977 concerning the mutual assistance by the competent authorities of the Member States in the field of direct taxation, which initially established the legal basis for administrative cooperation in the field of direct taxation in Europe, the EU Savings Directive laid the groundwork for an enhanced exchange of information amongst EU Member States in tax matters. It coincided with savings taxation agreements with non-EU countries, that covered similar measures. These so-called Third Countries were the Swiss Confederation, the Principality of Andorra, the Principality of Liechtenstein, the Principality of Monaco, and the Republic of San Marino.

Austria, Belgium and Luxembourg did apply the automatic exchange of information at the same time as the other twelve EU Member States. These three Member States applied a withholding tax to the savings income during a transitional period. The withholding tax rate increased progressively to 35 %. Another outcome of the negotiations related to the EU Savings Directive was that Austria, Belgium and Luxembourg were not obliged to apply the automatic exchange of information before the Third Countries ensured effective exchange of information on request concerning savings income.

On 15 February 2011 the Economic and Finance Ministers Council (ECOFIN) adopted the EU Directive on administrative cooperation in the field of taxation (EU Directive 2011/16/EU), which is referred to as the DAC 1 Directive. This Directive repealed and replaced Directive 77/799/EEC. The aim of DAC 1 was to enhance the administrative cooperation among EU Member States through an exchange of specified information in three forms: spontaneous, automatic and on request.

The most disruptive out of all these forms of exchange of information at the time was the automatic exchange of information because it required a certain administrative readiness. It has been applied to cross-border situations, where a taxpayer is active in another country than the country of residence. In such cases tax administrations automatically provide tax information to the residence country of the taxpayer, in electronic form on a periodic basis. Five categories of income and assets were initially targeted, namely employment income, pension income, directors’ fees, income and ownership of immovable property and life insurance products. The scope has later been extended to financial account information, cross-border tax rulings and advance pricing arrangements, country by country reporting and aggressive tax planning arrangements. The question whether the information provided amongst EU tax authorities has been consistently analysed and used for investigations to combat tax fraud is debatable. It is also questionable whether DAC 1 had the deterrent effect that it aimed at, and whether it actually dissuaded taxpayers from omitting tax relevant information in their tax returns, notably those holding assets in an offshore bank account. The efforts to improve the effectiveness of the exchange of information remained and continue as of today. Since 2011, the DAC 1 Directive has been amended multiple times. The most recent directive is referred to as DAC 8 whose objective is to ensure taxation of income stemming from crypto-assets and e-money and to implement OECD’s Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework at EU level.

As mentioned, a stricter legal framework to combat money-laundering, corruption, financing of terrorism, and drug trafficking was an important building block of the reform package that followed the financial crisis. A new AML regulation, referred to as the 4th AML Directive was adopted at EU level. As part of this regulation, tax crimes were considered as primary offence in the meaning of AML regulations. The 4th AML Directive called for important changes to the Luxembourg general tax law, namely the definition of tax fraud and its sanctions.

Developments at OECD level

An important development that coincided with the introduction of DAC 1 was the amendment of most double tax treaties, that Luxembourg had entered, such that article 26 of the OECD Model Tax Convention was introduced. There were good arguments for including a provision about cooperation between the tax administrations, especially to demonstrate Luxembourg’s commitment of exchanging information beyond EU borders. It also set the basis for a reciprocity in relation to the supply of information amongst treaty countries.

An additional initiative at OECD level, which is worth mentioning is the OECD Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information. It now counts 168 members, and is renown to be the leading international body fostering the implementation of global transparency and exchange of information standards around the world. The Global Forum supports its members in fighting offshore tax evasion and notably assisting jurisdictions to implement the international standards on transparency and exchange of information for tax purposes.

Another way of fighting tax evasion: The American approach.

The US tax regime differs fundamentally from most European tax systems because the tax liability is not based on tax residency but rather on citizenship. In 2010, the US government enacted its own set of rules to combat tax evasion by US persons holding investments in offshore accounts. This regulation is known as the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA). In Luxembourg, the FATCA Law requires entities to determine if they qualify as so-called Financial Institutions (“FIs”). FIs need to identify all US clients and investors and report them to the US Internal Revenue Service through the Luxembourg tax authorities. The definition of US clients in accordance with the FATCA Law is very broad. FIs must also gather data on the relevant account/capital balances and global income and proceeds pertaining to their US clients or investors. The FI definition does not only include banks, insurance undertakings and investment vehicles, but also some holding, financing, or securitisation companies.

FATCA followed a regulation that had been effective since 2001, the so-called Qualified Intermediary ("QI") regime. If certain conditions were met, it provided US withholding tax relief at source on US-sourced income paid through non-US banks acting as nominees on behalf of their customers. Under a Qualified Intermediary Agreement with the IRS, a QI committed to the identification and documentation of clients, reporting and withholding. With the introduction of FATCA ("Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act"), new requirements were imposed on financial institutions. In order to coordinate the obligations under FATCA with those of the QI regime, a revised QI Agreement was published in June 2014. Since the introduction of FATCA, the QI Agreement has been constantly subject to revision, requiring regular updates regarding documentation, withholding, and reporting of taxes as well as reviews of the internal compliance processes, policies, and procedures.

Different approaches to tax amnesty and how to deal with undeclared assets.

Some European countries entered into so-called “Rubik” agreements. These were bilateral agreements that aimed at ensuring the effective taxation of income stemming from undisclosed bank accounts held by foreign banking clients in Switzerland. The “Rubik” agreements also provided for the possibility of maintaining anonymity of the taxpayer going forward. Apart from Germany and the UK, other countries in Europe signed such agreements.

The "Rubik" Agreement between the UK and Switzerland was signed on 6 October 2011, shortly after a similar agreement was concluded between Germany and Switzerland in September 2011. Some adjustments to the “Rubik” Agreement were subsequently required to ensure conformity with EU law, in particular the EU Savings Directive. The UK-Swiss “Rubik” Agreement provided for a tax amnesty for UK taxpayers who had evaded tax on income stemming from assets held in an undisclosed Swiss bank account. Why did the UK Government sign an agreement which allowed tax evaders to enjoy impunity on payment of a lump sum and continue to file incomplete tax returns in the future? In hindsight this is hard to explain, but the budgetary deficits linked to the financial crisis may have been a compelling reason.

Some EU countries had domestic tax amnesty regimes which allowed for the regularisation of undeclared assets of private banking clients holding offshore accounts. Those regimes provided the possibility to self-report to the tax authorities through corrected returns, which in turn guaranteed impunity from prosecution. These tax amnesty regimes have been existing in Germany, the Netherlands and Austria, just to name a few countries.

At Luxembourg level, the ICMA Private Wealth Management Charter of Quality was quickly issued and followed by the CSSF Letter dated 3 December 2012, which provided some guidance on how to deal with undeclared assets held by foreign clients at Luxembourg private banks. Whilst these initiatives were helpful for Luxembourg from a reputational viewpoint, they only represented a voluntary commitment. The content of these regulations were similar others, already existing at that time in terms of AML, KYC, MiFID and other CSSF circulars and the requirements remained overall quite vague. In summary, the ICMA Charter was a short-lived attempt to instil once more confidence in the Luxembourg financial market.

The short-term effect on Luxembourg banks: challenge accepted.

One of the primary short term goals of Luxembourg banks was to assist clients to regularise their assets in their respective country of residence. Active management and client base review was performed and decision had to be taken also to off-board clients not willing to confirm their tax status.

Furthermore, banks were concerned by ensuring compliance with the enhanced regulations and onboarding processes, notably with constantly growing AML rules as well as tax rules in the various countries of residence of their clients.

Data security and fraud prevention was a huge concern because of data theft cases observed in other countries. Those required a review of the entire IT environment and mostly an enhancement of (client) data security.

Last but not least operational readiness to exchange tax information to countries of residence was had to be achieved and to tax reporting packages had to be provided to clients according to the requirements of their country of origin, which was another challenge.

How were the banks affected in the long and medium term?

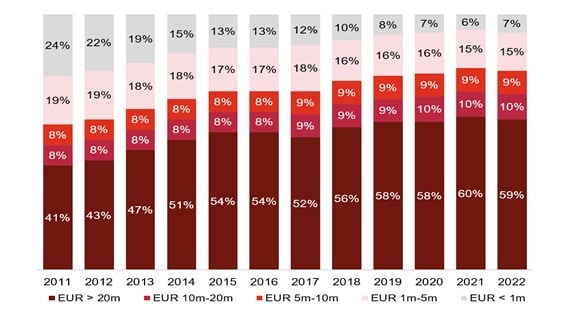

The business model shifted such that the client base moved from mass affluent to (ultra) high net worth individuals. Besides the value of assets, the nationality of the clients changed, and banks started offering enhanced wealth structuring services. Accordingly, the skill sets, and qualification of the bank employees changed considerably moving away from a product focused CRO base serving a huge number of clients (up to 500 in some cases) towards an advice and structuring focused advisor model requiring a wide range of skills in legal, tax and structuring matters. Important changes were also required regarding operations and compliance, such as the introduction of a tax control framework, internal governance, policies, and procedures to comply with exchange of information requirements. The provision of client tax reporting documents is an industry standard nowadays, a must have. However, the latter comes along with a high complexity depending on the clients’ country of residence and a wide range of tax regimes to be covered.

A solid tax control framework is also helpful in light of the personal liability of the directors, which can be involved when they gain knowledge of or even aid tax fraud.

Prior to the lift of the banking secrecy, Luxemburgish Private Banks targeted mainly neighbouring European countries such as France, Belgium and Germany. Since then, they expanded their client base mainly in Europe, which as of today accounts altogether for more than two thirds of the private banks’ client base, excluding Luxembourg. Today, as the European Private Banking Market approaches maturity, Luxemburgish Private Banks expand their client base globally, targeting attractive markets for instance also in Asia, South America, Middle East and other regions in the world.

One other element of the transformation that took place after the lift of Banking Secrecy was a market consolidation. Whilst some banks decided not to transform and left the country, others actively grew their client base via proactive M&A activity and a purchase of client portfolios from other banks.

How is the industry doing today?

The Luxembourg Private Wealth Management industry has successfully managed the necessary transformation following the arrival of exchange of information. This transformation came along with a substantial shift in the client base moving from mass affluent client towards high net worth clients and family offices. Despite a massive drop in the number of clients, the Assets under Management in Private Banking has not dropped, but in contrary has envisaged a significant growth path during the past ten years.

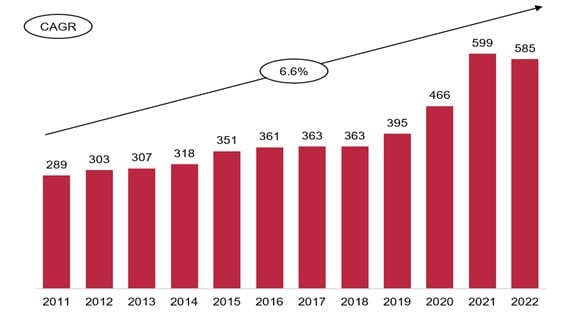

Private Banking AuM in Luxembourg (EUR bn)

Evolution of the distribution of client wealth bands (% of AuM)

Source: ABBL - PwC, November 2023

This shows that Luxembourg’s banking sector maintains a robust and dynamic landscape through sustained asset growth and evolving client-centric strategies. One of the biggest changes is that private banks in Luxembourg are now serving a new client base. The transformation that took place since 2010 also came with a reorientation towards the real strengths of Luxembourg as a financial center being Europe’s largest fund center enabling sophisticated wealth structuring via a range of tailored vehicles and providing an unrevealed ecosystem of experts in legal structuring, international tax advice, regulation and assurance.

Wealth structuring and succession planning are key elements of the service offering today. Luxembourg is an ideal place because of its wide double tax treaty network, availability of corporate structures and vehicles, including different levels of product regulation available. The ecosystem supports the industry such that qualified, and highly specialised service providers are present and capable.

Assets in Private Wealth Management reached EUR 951.7 billion at the end of 2021 and the Assets under Management of Luxembourgish Private Banks grew at a compound annual growth rate of 6.6% since 2011, reaching EUR 585bn as of the end of 2022.

Moreover, the private banking industry has also moved more towards a fee-based advice model since 2015 and after the arrival of MiFID II, where clients are charged directly for investment management and advice.

This shift away from the historical free service, where revenue was mostly generated from transaction-based commission and execution fees, has led to the growth of two main offerings: discretionary portfolio management (DPM) and advisory mandates.

The development of Luxembourg’s banking sector after the arrival of exchange of information is undoubtedly a story of successful transformation and client orientation. It required the market actors to be agile and to respond to new requirements at large scale, which they undoubtedly achieved with great success.

What to expect going forward

Luxembourg's private banking business has been growing during the past ten years despite the disruptive changes the industry had been facing after the end of banking secrecy. It is to be expected that this growth path will also be pursued going forward considering the need for and the growing complexity of international wealth structuring, which is at the heart of Luxembourg's value proposition in Private Wealth Management. Tax compliance of the underlying business is essential in this.

The tax and regulatory changes which we have been observing for the last ten years are irreversible. The complexity of international tax and transparency laws is constantly increasing; and so is the scrutiny of the tax authorities. Considering the looming economic downturn in Europe, we do not only expect the number of tax audits in Luxembourg to increase, but also the initiations for tax offence proceedings, leading to soaring liability risks for corporate bodies and executives, which also result in additional reputational risks. These evolutions require a strong governance and control framework. Banks are advised to establish their own tax strategy, assign clear responsibilities within their organizations and to thoroughly document their governance. These elements will be a first line of defence in the event of tax audits and mitigate the risks for both the organizations as well as their executives.

Contact us

Murielle Filipucci

Tax Partner, Global Banking & Capital Markets Tax Leader, PwC Luxembourg

Tel: +352 62133 31 18

Nenad Ilic

Tax Partner, Banking & Capital Markets Tax Leader, PwC Luxembourg

Tel: +352 62133 24 70

Julie Batsch

Audit Partner, Banking and Capital Markets Leader, PwC Luxembourg

Tel: +352 62133 24 67

Jörg Ackermann

Advisory Partner, Banking Consulting Leader, PwC Luxembourg

Tel: +352 49 48 48 4131