Application of the EU Taxonomy in Banking and Portfolio Management

Introduction

The EU Taxonomy, a classification system for environmentally sustainable economic activities, was published in the Official Journal of the European Union on 22 June and entered into force on 12 July, 2020. The first delegated act on sustainable activities for climate change and mitigation objectives was approved in principle on 21 April, 2021, formally adopted on 4 Jun, 2021, and aims to direct investments towards sustainable projects and activities. One question that has not yet been fully answered in this context is to what extent banks can apply the taxonomy in relation to their core business models. In the following, we would like to use the example of financing a solar power plant to explain the questions when applying the EU taxonomy and also to shed more light on the advantages and the particular challenges.

What conditions must be met when applying the taxonomy?

The taxonomy comprises a framework with four overarching conditions an economic activity needs to meet in order to qualify as environmentally sustainable.

Condition 1 ‘substantial contribution’: The solar power plant substantially contributes to at least one of the six environmental objectives established in the regulation: (1) Climate Change Mitigation (2) Climate Change Adaptation (3) Sustainable Use and Protection of Maritime Resources (4) Transition to a Circular Economy (5) Pollution Prevention and Control (6) Protection and restoration of Biodiversity and Ecosystems. By generating electricity using solar PV technology, the plant provides energy to households and businesses without increasing its, or their, environmental footprint but promotes the mitigation of climate change. The undertaking needs to be in compliance with quantitative and qualitative Technical Screening Criteria specific to the business activity.

Condition 2 ‘no significant harm’: The needs to be conducted to ascertain that the positive contribution to one environmental objective does not cause any harm to the attainment of the other EU objectives. Specific risks are set out. Renewable energies promote a change towards sustainability as to how existing and new technologies, products and processes are powered, and thus, they assist in adapting to climate-induced changes. A solar plant is an ideal example to depict a circular economy, a loop in which components can be repaired and are exchanged as little as possible, and even then given a second usage. Furthermore such plants can be integrated into ecosystems without the need to sacrifice the natural habitats of different species, and without polluting water areas or the air. The delegated acts develop the technical screening criteria that shall be met by a solar plant to demonstrate the substantial contribution (Condition 1) and the DNSH test (Condition 2).

Condition 3: The business activity needs to comply with minimum social safeguards. Here, this means conducting business responsibly as per the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and recognising the role of solar power plants as a society´s specialised organs that perform functions to secure the human well-being without harming the environment or human and non-human lives.

What are the advantages of using the taxonomy?

As a market participant, the choice of approach is to invest into sustainable investments pursuing social goals or non-EU defined environmental goals or to invest in accordance with the EU environmental goals, i.e. following EU Taxonomy. The taxonomy sets a common set of definitions and thresholds and as such, the banking sector is subject to higher standards in terms of consistent, transparent and comparable reporting on green financial products and processes. Green loan principles are now being fully replaced by the taxonomy that:

Scales down reputational risks, and more importantly, environmental risks, through harmonised reporting, directly impacting the stakeholders’ perception of the bank;

Offers banks the possibilities to create additional value and differentiate from the crowd, ultimately leading to more confidence by clients and further business opportunities through partnerships with larger institutions;

Enables banks to directly reflect on their impact on the environment and society leading to crucial self-awareness

Includes a homogeneous segmentation process for clients, strengthening risk management practices, enhancing due diligence and resilience to environmental and social risks;

Requires client businesses to report on sustainability indicators, too, affording a drastic improvement of corporate data availability and quality.

What are the challenges in applying the taxonomy?

Applying the taxonomy in practice also leads to some challenges for banks. As the application is just starting, there are clearly gaps between existing company internal requirements and requirements given through the taxonomy. A global mutual understanding of sustainable products and practices will take time and an implementation of taxonomy thresholds is a key requirement. The current established practices require less sustainability-related reporting and thus, a general lack of carbon emission data causes difficulties in the assessment of technical screening criteria. Potential issues can occur through differences in the current stage of investments in renewable energy sources, lack of incentives to information reporting or lack of pollution thresholds set by government agencies. Overall, increased documentation, monitoring and time is necessary to complete and monitor the use of proceeds.

In the above example of a solar plant, the DNSH test will require information about the durability and recyclability of equipment and components as well as an environmental impact assessment.

Small enterprises can experience certain limitations in disclosing taxonomy-relevant information due to lack of resources, expertise and incentives on providing data. They are often restricted in the access to adequate information that leads to making imprecise assumptions about sustainability measures of clients’ businesses and the assessment of screening criteria. A major upgrade in banks’ internal information processes and IT infrastructure is necessary due to an increased data input. Systems need to be adapted to be able to inspect clients and their value chains when anticipating the taxonomy incorporation. The truthfulness of sustainability related certificates is often only vaguely verified and needs to receive special attention. To anticipate the taxonomy implementation, banks should act as a self-starter and collect methodical data.

A further requirement for successful taxonomy use is the education of employees on sustainable business practices and taxonomy related requirements. A practical understanding of the fundamentals of its applicability can be achieved through expert seminars and mandatory online training. As a result, banks should get a holistic view on all clients processes through an understanding of their entire value chains instead of just final products.

Practical steps to consider when applying the taxonomy?

Specifying the use of the proceeds. This may require the bank or portfolio manager to gain a comprehensive understanding of the client's value chain, instead of only the end product. If the purpose cannot be specified, the bank or portfolio manager needs to classify the exposure based on the client's business activities or limit the application to products with a specified use of proceeds.

Examining the taxonomy eligibility of the business activity by identifying the environmental objective contributed to, doing DNSH tests and assessing the compliance with minimum social safeguards. The bank or portfolio manager might need to acquire additional data and/or require more data from its customers or targets.

Disclosure of information for Technical Screening Criteria by the client in a format easily accessible to check whether these criteria are met.

During the transition period, assuming the client complies with relevant legislations. Reliance on certification schemes, third party assurance and labels whilst ensuring potential gaps are filled through bank or portfolio manager research, or, in case of immaterial issues at stake, closing the transaction while the assessment is still ongoing.

Engaging with sustainability experts and upskilling teams on sustainability.

DPM / Portfolio management

Encouraging investors to re-orient funds towards more sustainable opportunities, the comprehensive EU regulation has taken another great leap forward when it comes to Portfolio Management Services offered by a bank. The European Commission has made a series of publications, focusing on three key topics which affect these aforementioned business models:

EU Taxonomy Climate Delegated Act: aiming to provide a common framework to the definition of a “sustainable investment”. The outline of two of six “environmental objectives” are finalised, the others are following in 2023;

Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (“CSDR”): displaying proposal for amending the existing Non-Financial Disclosure Regulation (“NFDR”) framework, regarding the scope of companies included, to enhance valuable sustainable finance data on investee companies available for the financial sector ;

Sustainability preferences and fiduciary duties: encompassing six amending Delegates Acts that touch investment and insurance advice, ensure the inclusion of sustainability in the processes and procedures of investment advisors, asset managers and insurers.

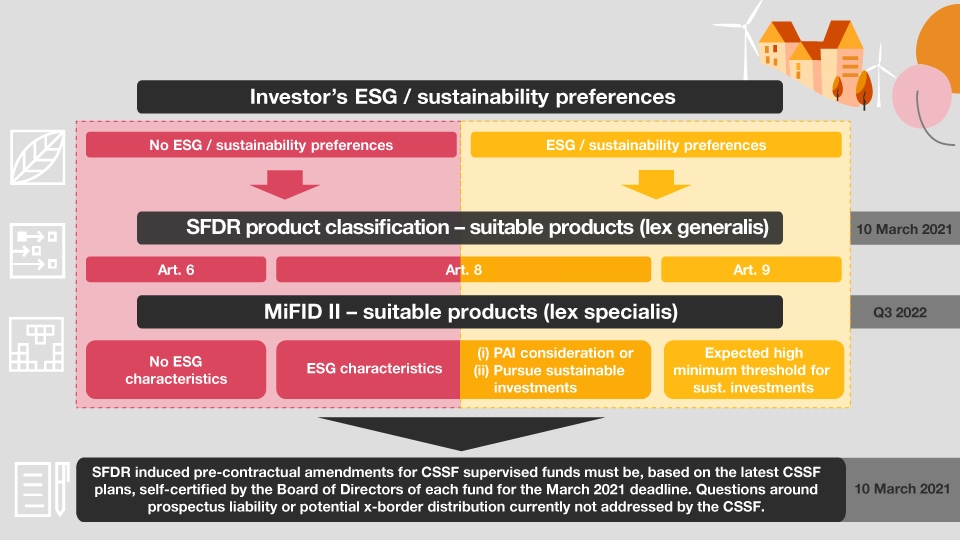

From a banking perspective, in particular it will be interesting to identify and assess the implications of the latter of these three regulatory developments in the context of portfolio management activities. More precisely, the amended Delegated Acts of Sustainability preferences and fiduciary duties touch upon two key features of the MiFID Investor Protection framework: First, there is the integration of clients’ preferences in terms of sustainability as a top up to the suitability assessment. Second, suitability or ESG factors are to be integrated within the Target Market framework, from a manufacturer as well as from a distribution point of view.

Today, non-financial considerations such as sustainability preferences are very rarely part of the suitability assessment, and studies have shown that end-investors in general are little knowledgeable about the sustainable finance service and product shelf of their bank. At the same time, the market is characterised by a wide variety of financial instruments with a wide-variety of sustainability ambitions; ranging from “best-in-class”, deep green investment strategies to basic exclusion approaches. Furthermore, defining the “sustainability preferences” from a regulatory perspective means having to align the underlying logic of MiFID II with the product scope of SFDR and taxonomy.

Based on this background, the regulator has defined suitability preferences as comprising financial instruments that are either (i) invested, at least to some extent, in taxonomy-compliant activities or (ii) in sustainable investments as defined by the SFDR or (iii) that consider negative externalities of investment on the environment or society in terms of principal adverse impacts on sustainability.

Properly deciphering this regulatory jargon and transmitting it to the investor will be key in assessing and identifying an investor’s actual suitability preferences.

From a practical perspective, this means that banks will have to collect information about their client’s appetite for sustainable investment and develop a fitting service and product-shelf. While the regulator expects that sustainable preferences are included within the suitability framework, it appears that the actual profiling is not impacted. It is put forward that MiFID firms providing advice or discretionary portfolio management should first assess a client’s “other” investment objectives, time horizon and individual circumstances, before asking about the applicable sustainability preferences. As such, it is to be assumed that the suitability preferences become an additional suitability constraint within the suitability test logic.

As such, the form of the integration of the sustainability preferences will depend to a large extent on the existing control framework; suitability test at portfolio vs instrument level and suitability test only at transaction vs. on-going basis.

In parallel, banks (in their role as product distributors) or portfolio managers, will have to integrate the notion of suitability preferences into their Product Governance Framework and as such into their Target Market controls. This exercise will entail mapping product characteristics to client needs and objectives. A prerequisite for this exercise, is that both manufacturers and distributors find an alignment in their interpretation of the suitability preferences and respectively transpose this alignment in their product approval (manufacturer) and distribution process (distributor).

One key issue here is that products such as investment funds that disclose their environmental and social characteristics under the Art.8 SFDR regime, do not necessarily qualify as sustainable investment as defined within MiFID II. Put differently, a fund may pursue an investment strategy that promotes environmental and social characteristics, but that does not invest in sustainable investments. Such instruments cannot be sold under the new MiFID II rules to clients who have expressed “sustainable preferences”, as the latter is linked to sustainable investment and Art.8 investment strategies may be wider than sustainability investment oriented.

This complexity is summarised in the below graph, with the right hand side representing sustainable investments aligned with MiFID II definitions and the left hand side representing investment that are not in line with MiFID II sustainability preferences:

While the amended MiFID obligations are not foreseen to be applicable before Q3 2022, the need for action is imminent. As seen during the MiFID II implementation, updating the client questionnaire, planning and organising a client outreach, updating service models and control frameworks as well as aligning interpretations between manufacturer and distributor can be time and resource consuming activities.

Yet dealing with the MiFID amendments is only one of many action points on the still long and exciting sustainability journey.

Conclusions

There can be observed a rather large gap between the current practice of banks and the EU Taxonomy. It is hence recommended that banks follow a step-by-step approach, as the regulation is said to be more easily applicable to some sectors or products than to others.

The availability of data to assess the environmental impact of business activities might not always be given, but banks and portfolio managers can either purchase data sets from external sources or have the possibility to add a questionnaire along the credit approval process asking for specific ESG-relevant information. In particular, this is important when serving small businesses as they are not subject to large data collectors. The evaluation of the data currently still has more of an informative character. There is no immediate influence on the calculation of the probability of default. ESG-related criteria are already expressed in the second vote process - however, these also only have an informative character. In summary, one of the biggest challenges is access to new data, which in turn forms the basis for considering sustainability-related risks. In addition, there are new reporting obligations for the sake of additional transparency. As a conclusion, implementing the taxonomy alignment measurement will be a challenging exercise that will affect all activities of the banks and portfolio managers, its own activities (starting with the lending activities but also investment and commission activities) in order to calculate the Green Asset Ratio (for banks) as well as its intermediaries activities, in order to ensure that financial products and portfolio meet their customer environmental preferences (for banks and portfolio managers).